Of all lifestyle behaviours, smoking caused the most deaths in the last century. Because of the time lag between the act of smoking and dying from smoking, and because males generally take up smoking before females do, male and female smoking epidemiology often follows a typical double wave pattern dubbed the ‘smoking epidemic’. Our research aimed to answer the questions: How are male and female deaths from this epidemic differentially progressing in high-income regions on a cohort-by-age basis? and How have they affected male-female survival differences?

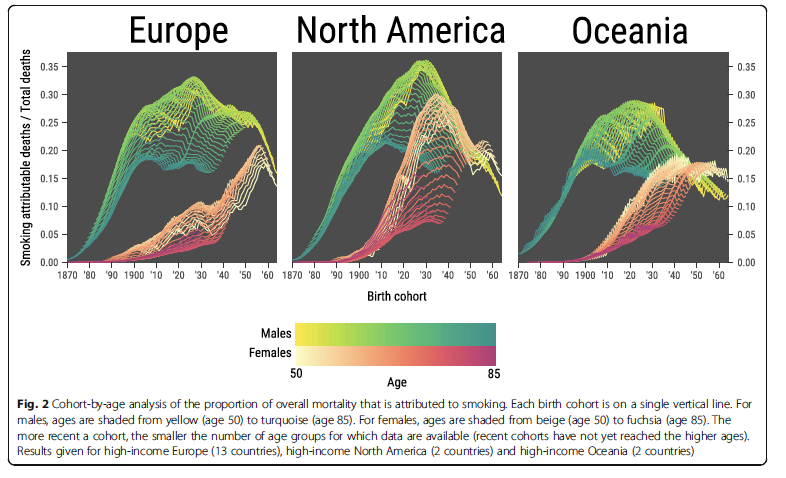

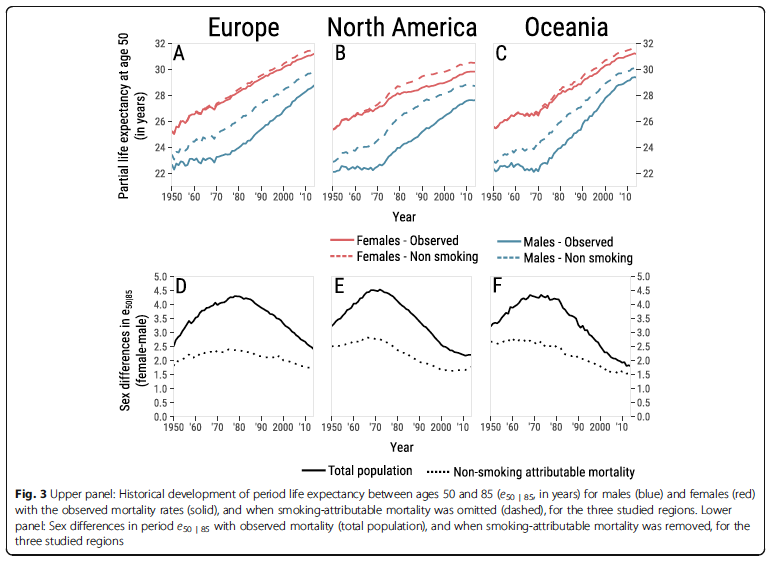

To answer these questions we used data for the period 1950–2015 from the WHO Mortality Database and the Human Mortality Database on three geographic regions that have progressed most into the smoking epidemic: high-income North America, high-income Europe and high-income Oceania. We examined changes in smoking-attributable mortality fractions as estimated by the Preston-Glei-Wilmoth method by age (ages 50–85) across birth cohorts 1870–1965. We used these to trace sex differences with and without smoking-attributable mortality in period life expectancy between ages 50 and 85.

We found that in all three high-income regions, smoking explained up to 50% of sex differences in period life expectancy between ages 50 and 85 over the study period. These sex differences have declined since at least 1980, driven by smoking-attributable mortality, which tended to decline in males and increase in females overall. Thus, there was a convergence between sexes across recent cohorts. While smoking-attributable mortality was still increasing for older female cohorts, it was declining for females in the more recent cohorts in the US and Europe, as well as for males in all three regions.

Figure 1: Cohort-by-age analysis of the proportion of overall mortality that is attributable to smoking, by geographic region.

Figure 2: Upper panel: Historical development of period life expectancy between ages 50 and 85, for males (blue) and females (red) with the observed mortality rates (solid), and when smoking-attributable mortality was omitted (dashed), for the three studied regions. Lower panel: Sex differences with observed mortality (total population), and when smoking-attributable mortality was removed, for the three studied regions.

Thus, the smoking epidemic contributed substantially to the male-female survival gap and to the recent narrowing of that gap in high-income North America, high-income Europe and high-income Oceania. The precipitous decline in smoking-attributable mortality in recent cohorts bodes somewhat hopeful. Yet, smoking-attributable mortality remains high, and therefore cause for concern.