People stop having children earlier than their biological clocks warrant. One of the reasons for the discrepancy between potential and achieved childbearing after age 40 could be social stigma. A study by Francesco C. Billari, Alice Goisis, Art C. Liefbroer, Richard A. Settersten, Arnstein Aassve, Gunhild Hagestad, and Zsolt Spéder documents the existence of social age deadlines for childbearing across Europe. At what age would you say a woman or man is generally too old to consider having any more children? That question was asked to more than 40,000 people across 25 European countries between 2006 and 2007. Drawing from the data collected as part of the European Social Survey (ESS), the authors of this study posit the idea that social norms discouraging later parenting could be (one of the factors) limiting fertility at advanced ages.

Biological possibility, social impossibility

In the EU, births to mothers aged 40 and over increased from 1.6 percent in the late 1980s to 3 percent in 2006. But these numbers are somewhat below women's biological potential. The analyses reveal the existence of upper age limits to childbearing, namely social norms against engaging in parenthood too late.

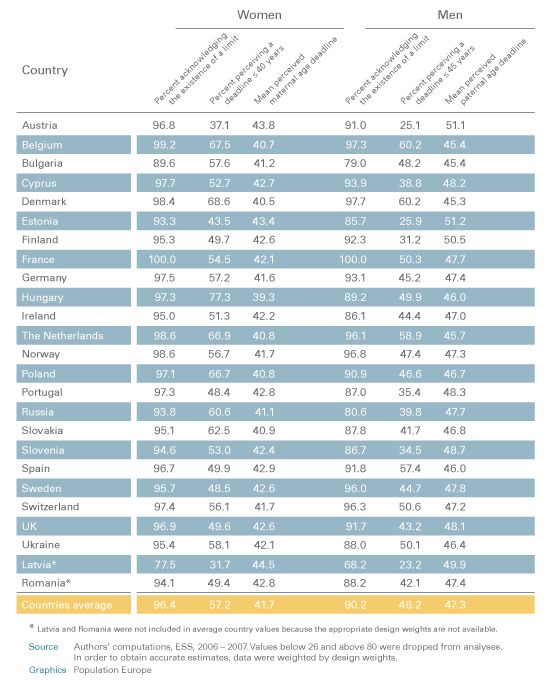

For example, in 16 of the 23 countries included in the analysis, the majority of people think women should stop having children when they are 40 or younger. The perceived mean maternal age deadline varies from 39.3 years in Hungary to 43.8 years in Austria. Men's deadlines are much higher - from 45.3 years in Denmark to 51.2 years in Estonia (table 1).

Table 1: Social age deadlines for the childbearing of women and men, by country.

One clear finding of this study is that, with the exception of France, the proportion of respondents who perceive an age deadline for women is larger than for men, The mean deadline for women hovers around 40 while for men it is closer to 50. The authors also note that there is less standard deviation in the deadlines for women. These results suggest that people have firmer ideas about when women should stop having children.

Times may be changing

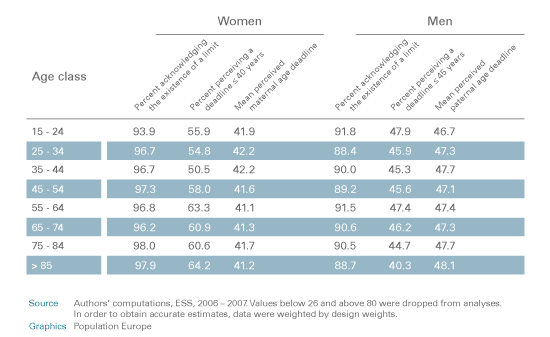

The responses to childbearing deadlines for women among younger people seem to be slightly weaker than among older people while the opposite occurs to childbearing deadlines for men such that the gap in deadlines between women and men is surprisingly small amongst younger respondents. One reason could be that young people in Europe are savvier regarding recent medical progress and they see fewer biological limits to procreation for women and more age limits for men. Alternatively, it is due to a different perception of gender equality: young people may believe in more equitable styles of parenthood than older generations. They are likely to apply similar expectations to women and men when it comes to having and raising children.

Table 2: Social age deadlines for the childbearing of women and men, by age group.

Context matters

The results reveal little variation across countries in terms of mean upper age limits, but considerable heterogeneity in both the percentage of people who perceive a deadline and in the percentage of people who feel that women should not have children after age 40 and men after age 45. These differences across Europe underscore the fact that social ideas about the ages at or after which it is inappropriate to have children are intimately conditioned by the cultural context. The authors also suggest that social age deadlines could, in part, reflect the development of medical technologies. Country-level correlational analyses reveal that countries with more fertility clinics per thousand women in reproductive age have lower proportions of respondents perceiving a deadline and higher mean maternal age deadlines to childbearing.

The findings from this study suggest that future research and data collection efforts should be directed at gaining a deeper understanding of social age deadlines, and of their interaction with reproductive behaviour.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.