Declining fertility rates have been at the centre of discussions in every developed country for a while now. Even though some European countries do not suffer from fertility rates below the replacement level, the trend towards late motherhood seems to be invariable. Due to this trend of postponing motherhood, significant proportions of women all over Europe have only one child or even remain childless. Massimiliano Bratti and Konstantinos Tatsiramos evaluate the effects of delayed motherhood in European countries and establish a connection between the trend of becoming a mother late in life and the possibility of having a second child.

The effect of delaying the first birth varies across countries. The impact in every country is different, depending on its institutional and socio-cultural features. In their study, Bratti and Tatsiramos focused on ten European countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the UK. Their analysis was based on individual, highly comparable data from the European Community Household Panel.

The outcomes of postponement

When it comes to delayed motherhood, there are two main pathways to follow - the biological and the socio-cultural effect. The biological consequence is the most obvious one: fecundity declines with age. Parts of this development can be slowed down by assisted reproductive technologies. But these technologies are not equally available throughout Europe – for example, there are strict rules in Germany, whereas there is a more laissez faire approach in Greece. Therefore, it can be assumed that the effect of biology may have different impacts in different countries.

Simultaneously, biology influences the socio-cultural effect. There is often maximum age that is normatively regarded as acceptable to become a mother. Depending on the norms and the environment in every country, these moral standards differ. Socio-cultural norms seem to play a more important role than biological reasons. This is why the availability of assisted reproductive technologies may not necessarily have a significant influence. Therefore, both the biological and the socio-cultural effect are likely to have an impact on the probability of having a second child especially if women delay having a first child.

The career effect

For working women, there is a third pathway that explains the postponement of motherhood. The effect of career planning assumes that working women have children only when they have attained their desired position in their respective careers or when they have gained enough work experience. Other factors that may be considered as career-motivated includes the assumption that women aim to not only have incomes high enough to bear the costs of having a child, but also to have enough money to tide over a phase of unemployment before starting a family. In contradiction to the earlier mentioned two pathways of biology and socio-cultural factors, the career effect can produce a “catch-up effect”. This means that there is a positive effect on the total number of children.

Successful women catch-up

Bratti and Tatsiramos examine the relation between delayed motherhood and the feasibility of achieving a second child. This relation varies across countries and also depends on the extent of women’s labour force attachment. If women with lower career ambitions delay the birth of their first child, they are generally less likely to have a second child. The “postponement effect” takes place mostly due to biological and socio-cultural factors. Interestingly, the case is different for career-oriented women. The “catch-up effect” is attributed to them as they are more likely to have a second child relatively late in life. For women who are strongly attached to their jobs, the career-orientated motive to delay their first birth generally gives them more work experience and higher earnings. As a consequence, this leads to their higher likelihood of becoming a mother for the second time. The effect is even more probable, the more successful a woman is. The higher the income and career-position are, the more does the positive career effect offset any negative biological and socio-cultural impacts.

These forces have different magnitudes depending on each country’s institutional features. In particular, the catch-up effect is smaller in countries with a traditional view of women’s roles. In societies where the “male breadwinner model” is still dominant, the “catch-up effect” is less likely to take place. On the other hand, a positive “catch-up effect” is greater in those countries that make it easier for women to participate in the labour market. Family-friendly solutions for maternal leave and child care have a positive and significant effect. Women who delay their first birth tend to later have a second child in countries where state subsidised childcare options are available and in societies in which part-time employment models are accepted.

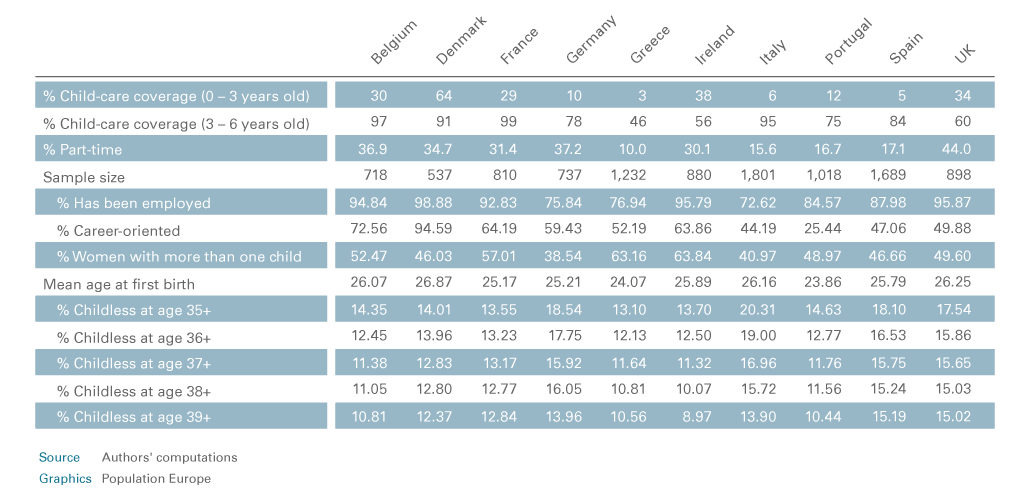

Table 1 shows a high coverage of childcare and availability of part-time employment opportunities in Denmark and France, while in Southern European countries such as Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain, access to childcare is limited and there is only a small proportion of part-time employment.

Table 1: Institutional details and summary statistics

The North-South Divide

The researchers show that the “postponement effect” is extremely high in Ireland and in Southern European countries. On the other hand, in countries such as Denmark, France and Germany the “catch-up effect” for working women is larger than the negative effects of biology and normative socio-cultural factors. The overall effect is even positive. However, in countries such as Greece and Portugal, where the positive career effect is relatively small, it is negative, which means that in total, fewer children are born.

Table 1 also shows the mean age at first birth. Amongst all women aged over 35, those from Greece and Portugal exhibit the lowest average age of first child birth. The authors trace this back to a stricter negation against very late motherhood in Southern European countries. This north-south divide seems to be related to family-friendly policies. It reflects differences between countries in which there is a traditional view of the role of women. Apparently, the more family-friendly and liberal a country is, the more likely it is that the “catch-up effect” will help balance some of the outcomes of the trend towards late fertility. European societies need to learn how to best handle this unstoppable trend. To do so, it might be beneficial to have a look at what their European neighbours are doing.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.