Europe is ageing rapidly, and in Sweden this development has been especially visible for some time now. By 2050 older people will form 26% of the population, and their incomes will be far from sufficient to cover for the public costs they cause say Tommy Bengtsson and Kirk Scott in a recent review article.

Consequences of an ageing population

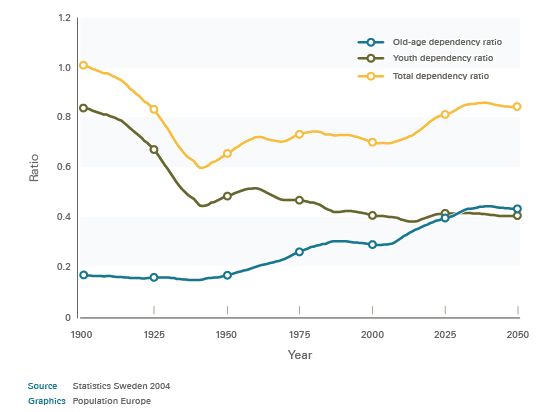

Current forecasts predict that average life expectancy will increase to 83 years for men and 85.5 years for women until 2050. The total fertility rate (TFR) will stabilise at 1.83 from 2009 onward. These changes will increase the total dependency ratio, e.g. the number of persons either too young or too old to work relative to the number of persons at working age (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Youth, old-age, and total dependency ratios for persons aged 20–65 years, Sweden 1900–2008 and estimates to 2050

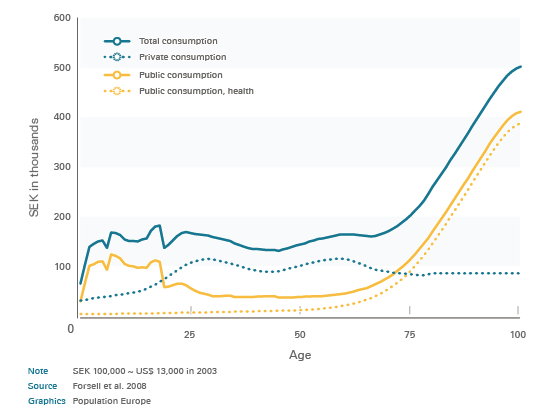

The authors also point out that consumption tends to exceed labour income once individuals reach their mid-sixties. By the time an individual reaches his 90s, his total consumption, meaning the costs that he or she generates, reaches € 35,000 to 43,000. That is twice as much as the average Swede consumes. A closer look at age-specific consumption indicates that the increase at older ages is due almost entirely to the cost of health care. The difference between these costs and the income of that age group is defined as the life-cycle deficit. In any given year, according to the authors, this deficit will have doubled in 30 years' time. Simply covering it and holding it at 2008 levels would require labour productivity to rise by more than 0.3%

(see figure 2).

Figure 2: Age-specific consumption, by type, Sweden 2003, measured in 2003 Swedish Krona (SEK)

With a growing share of the population spending more time in retirement, the pension system is also an important issue. The system was recently redesigned in order to keep the total cost of public pensions at a fixed rate of about 11% of the gross domestic product. However, the value of pensions will only stay stable in relation to the income of other age groups if the number of pensioners remains stable at current levels.

Demography will not solve the problem

Bengtsson and Scott argue that the problems caused by population ageing will not be solved by demographic developments. In line with most scholars, they do not believe that fertility rates will increase more than marginally in the future. And even if these numbers were to rise, this would have a limited impact in the near future.

Migration is the other potential solution to population ageing, and Sweden has been a country of net immigration since the 1930s. About 25% of the Swedish population today was either born abroad or has at least one parent who was born abroad, with 14% being first-generation immigrants. However, immigration has not played as large a role as perhaps expected in "correcting” the age structure. Female immigrants tend to adapt to Swedish fertility patterns very quickly. Moreover, since the 1970s, immigrant integration into the labour market has not been as successful as it had been earlier. In 2001, the actual unemployment rate was roughly 30% for immigrants and around 18% for natives. Even if it is possible to successfully navigate all potential integration problems, it remains unclear whether the economy would be able to absorb the massive increase in the labour force necessary to offset population ageing. Instead, the recent phenomenon of “jobless growth” in Sweden points to a further obstacle to this massive import of labour.

More taxpayers wanted

Sweden already has one of the highest taxation rates in the EU. Therefore the authors see little room for the government to increase them further in order to pay for the costs of population ageing. They argue that such a policy might cause the emigration of taxpayers to “cheaper” countries. That could even result in a net decrease in tax revenues because there would be fewer people to pay them.

Instead, Bengtsson and Scott suggest increasing the number of taxpayers by mobilising the potential workforce so that a greater share of those of working age actually works.

Getting young adults into the labour market as quickly and completely as possible is especially important. Combined with an increase in the retirement age and the number of working hours it might even be possible to not only maintain current living standards for future generations but to improve them.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.