Childcare has been more and more frequently included in European policy agendas; questions such as ?who should care for children, how, how much and for how long? are at the centre of the policy debate. Chiara Saraceno seeks to contribute to this discussion by comparing current childcare policies within Europe. The author also reflects on the debate on childcare from different angles, including work-family reconciliation, equal opportunities between genders, and inequalities among children. By combining these three dimensions, Saraceno concludes that childcare is not a matter of a simple division between family care, more specifically motherˆs care, and non-family care.

A new childcare paradigm

The so-called male-breadwinner family, characterised by a strong gender division, where fathers are barely responsible for taking care of their children and mothers are not expected to participate in the labour market, has been a fairly recent arrangement. This model prevailed in practice and particularly at the normative level in the Western European countries in the first decades following World War II. Since the Eighties and Nineties, however, due to changing gender roles and emancipation, a new normative model has been developed. In this model, mothers are encouraged to participate in the labour market while fathers are expected to more actively participate in childcare. It is also accepted that very young children will be (partly) taken care of in non-family care services.

Cross-country differences in Europe

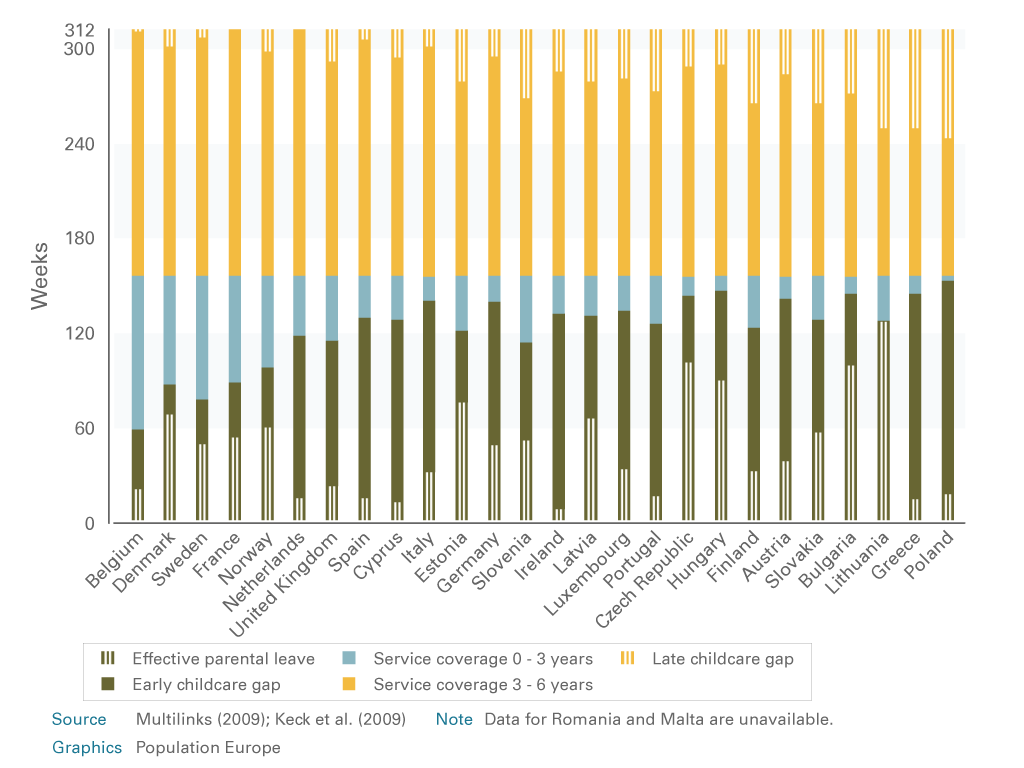

Despite the formal support to this new normative model by policy makers across the EU, there are still important cross country differences in childcare-related policies and realities. Saraceno argues that while “some kind of formal, non-family care and education” for children aged 3 to 5 is fairly widespread across all EU countries, there are significant cross-country differences in the provision of childcare for children under 3 years of age. Publicly supported childcare may be provided either through paid and unpaid leaves, and through services. All countries provide a combination of the two, but the country specific combinations differ both in their composition and in the amount of time/care covered. Differences in the “child care gap”, that is in the amount of weeks covered neither through leaves nor through services, are greater for children under three than for older children, thus making it difficult for young mothers in the less generous countries to remain in the labour market. The extremes are represented by Denmark and Poland.

Since leaves may be paid or unpaid (or little paid), thus offering different options to parents, the author uses a ‘effective leave.’ Effective leave is a measurement that combines compensation levels and the duration of parental leave. She also considers whether there is an incentive for fathers to take part of the leave.

Figure 1: Childcare coverage through ‘effective leave’ and publicly financed services, in working weeks, EU and Norway 2003-7

The former communist countries, except Poland, have the longest effective leaves (see figure 1), but no incentives for fathers to take that leave. A reserved quota for paternal leave is only found in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden. The lowest levels of support in terms of effective leave, particularly for children under three, are observed in Poland, Ireland, Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, and to a lesser extent in the Netherlands. However, in some of these countries, such as Portugal and the Netherlands, there is a high participation rate of mothers in the labour market. In the Netherlands, this achievement is explained by the possibility of working part-time, while in Portugal high labour market participation is enabled by the higher availability of support with childcare from extended family.

Mothers’ labour market participation: a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’?

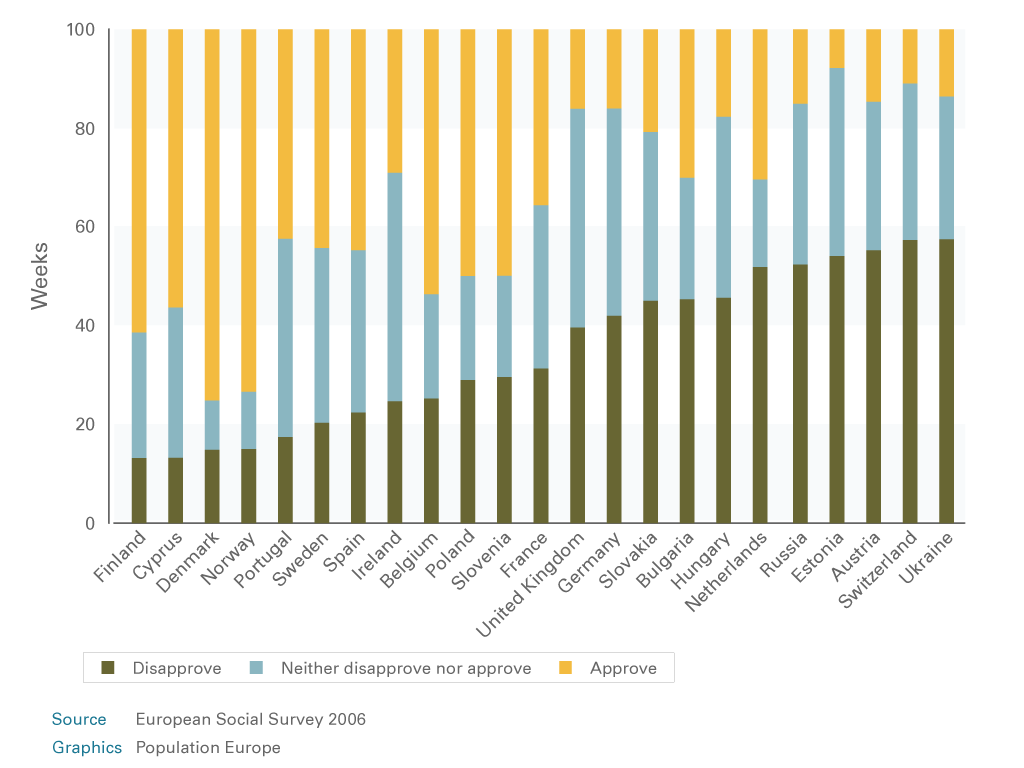

Cross country differences in policies may be partly the consequences of the prevalence of different cultural and normative models among the population.

When opinions regarding the question “should women with a child under three have a full-time job” are considered, as can be seen in figure 2, country differences emerge, which may partly explain the different policy approaches. Highest levels of approval are observed in the Nordic countries and Cyprus, while the highest levels of disapproval are found in the former communist countries and some central European countries such as Switzerland and Austria. Based on various empirical sources, Saraceno argues that preferences and values are embedded in specific contexts. Thus, there may be a circular feedback between policies and preferences/values.

Figure 2: Approval/disapproval of a woman with a child under three having a full-time job

Children in the forefront

The role of mothers as major caregivers creates not only gender inequality in the labour market but also a specific risk of poverty among mothers and children. Policies that have targeted these problems do so by (1) granting special protection and financial support and (2) encouraging and supporting mothers to enter the labour market. Recently, Europe has started to observe a shift from the first type to the second type of policies.

Furthermore, there is a nuanced picture when studying the outcome of attending formal childcare services at a very young age on well-being. In this regard Saraceno concludes that what matters is adequate parental care in combination with good quality and stable service, rather than age.

What shall we keep in mind?

When debating childcare needs and policies, it is important to keep in mind that subjectivities, context, and social relations are closely interwoven. The aforementioned cross-country differences are the result of a mixture of cultural values concerning obligations and children’s needs, opinions about labour market and social policies, and the availability and significance of kin networks. Furthermore, non-mother care can occur in different forms, and similar to the decision regarding whether and when to (re-)enter the labour market, it is influenced not only by policies but also by demography, geographic proximity, the marketing of services, intergenerational models, and economic means.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.