The dramatic increase in the human lifespan allows a radical rethinking of how and when we work, learn, and raise children. Even though in countries with the highest life expectancy almost half the children born since 2000 have a good chance to see one hundred, our expectations of life and work have yet to alter. Research by James W. Vaupel suggests more work-life flexibility.

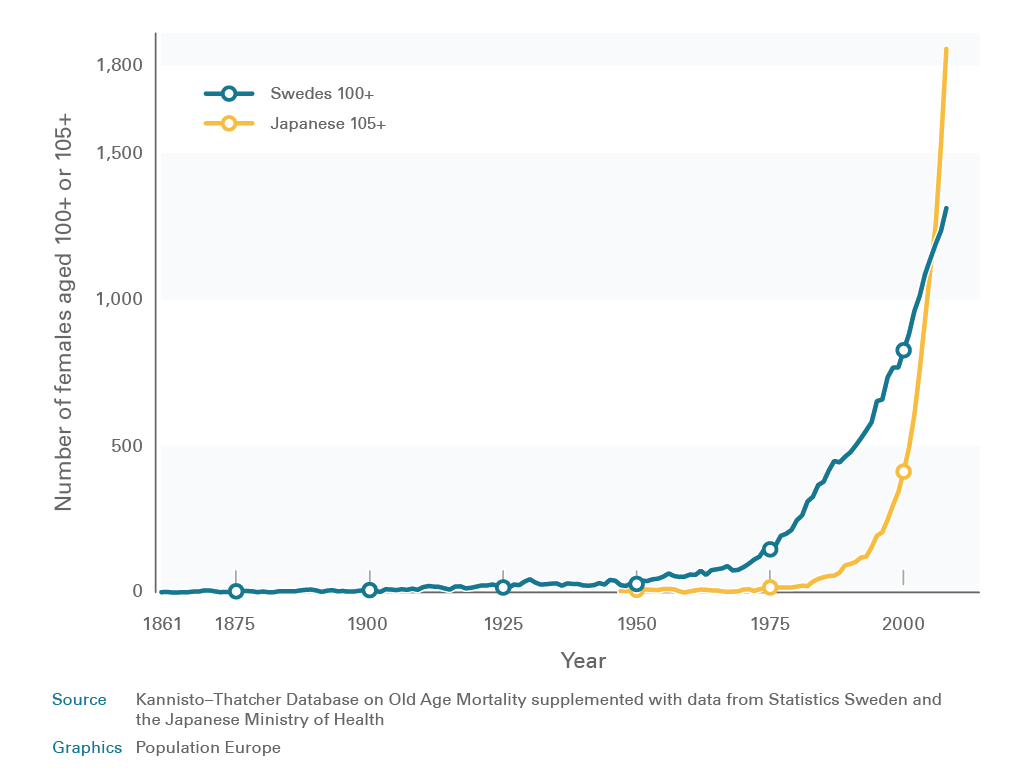

People are living longer. Life expectancy has increased by 2.5 years per decade. Sweden's changing population is a good illustration of this trend. Sweden has long kept track of its population make-up, and an examination of these records shows that in the early 1860s, three Swedes each year celebrated their 100th birthday, whereas in 2007 more than 750 did. Similarly, in Japan the number of women 105 or older has climbed exponentially.

This figure shows the number of females aged 100+ in Sweden from 1861 to 2008 and aged 105+ in Japan from 1947 to 2007

Rethinking life patterns

Vaupel points out that if young people knew that they would probably live past 100 and enjoy good mental and physical health for 90 to 95 of those years, they would probably organise their lives differently from past generations with dramatically shorter life spans. However, though life expectancy is rapidly increasing, there has not yet been a profound rethinking of how we live and work. In many countries, particularly those in which people live the longest, individuals devote most of their time to paid work at an age when they could have and raise children. They then retire from paid work at an age when their children no longer need them. The current pattern of spending two or more decades to education, the next three or four decades to trying to combine work and family, and then focusing on leisure for possibly two or more decades might seem less desirable than mixing education, work, child rearing and leisure across various phases of life.

Maintaining the work force

A rethinking of current work practices is also advisable given population change in many prosperous countries. In Germany, for instance, population decline and population ageing due to demographic change also mean that the workforce would decline. Thus additional work hours have to be supplied to maintain the output of the German economy. Current policies attempt to bridge this gap by increasing employment among people in their late 50s and early 60s or postpone age of retirement. However, these policies have caused great debate and are unpopular overall.

Vaupel suggests a sensible alternative for the future: Younger people should be compensated “for working when they are older by allowing them to work fewer hours per week over the course of their lives. The total output of the German economy can be maintained if citizens work more years but fewer hours per week.”

The political potential of biodemography

If the twentieth century was characterised by the redistribution of wealth, the twenty-first century will probably be the century of the redistribution of work. But though many policy-makers realise that the world’s population is ageing, the pace of this change and its social, economic and health-care consequences have not been adequately recognised.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.